NYTimes’ “The Choice” blog has an interesting piece titled “Remembering When College Was a Buyer’s Bazaar” which contrasts university admissions policies and practices between the late 1800s to now.

For example, did you know that top universities such as Harvard and Columbia used to advertise for students right up to opening day and offered entrance exams the weekend before classes started to give students every chance of taking and passing them?

And that Harvard even downplayed the difficulty of its entrance exam in advertisements, noting that of the 210 applicants who took its test in June 1869, 185 were admitted?

(Don’t ask me about my own college application process. Suffice it to say, I was deferred, wait-listed, then rejected from my top choice school. Triple rejection. Ouch.)

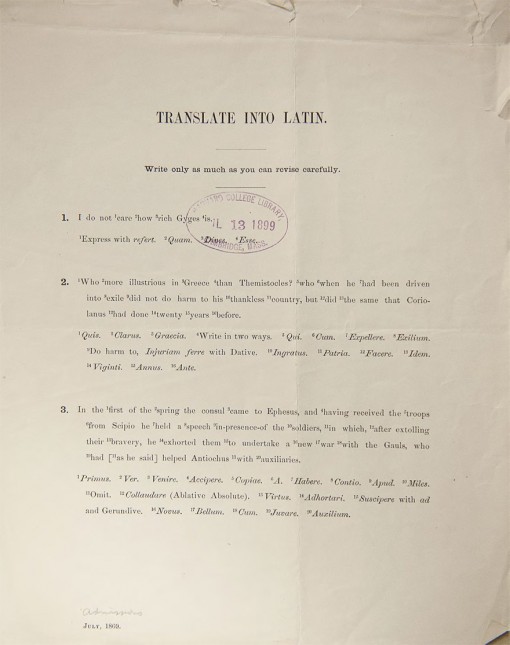

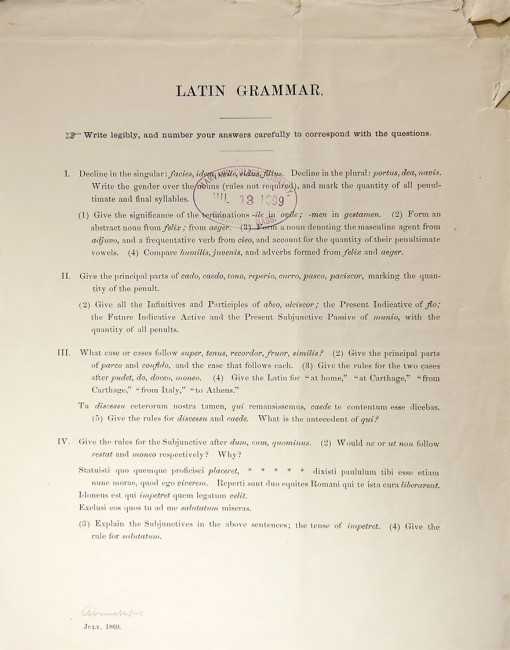

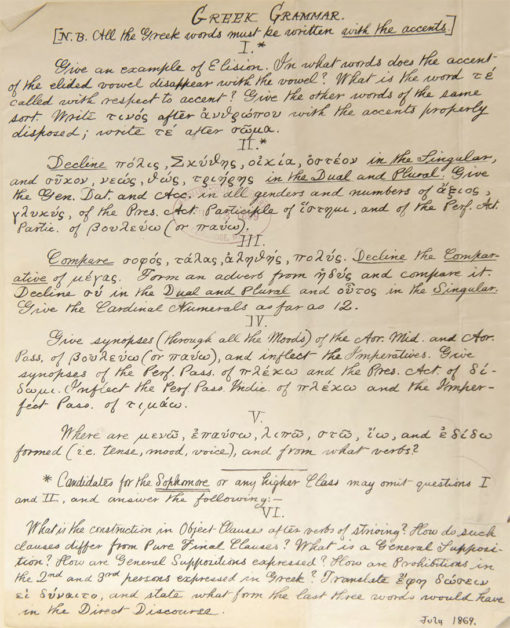

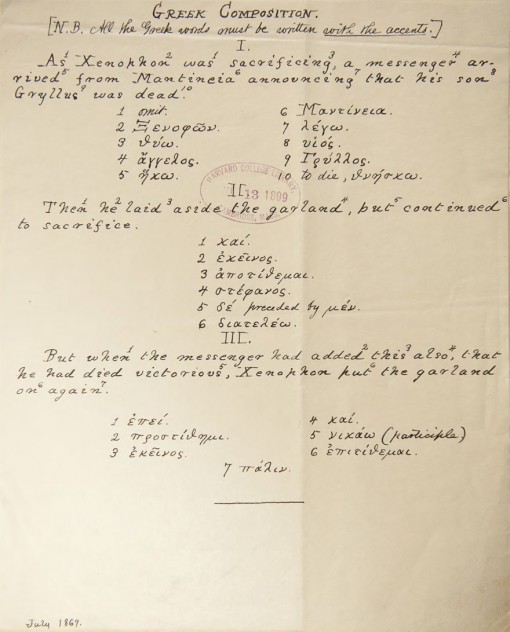

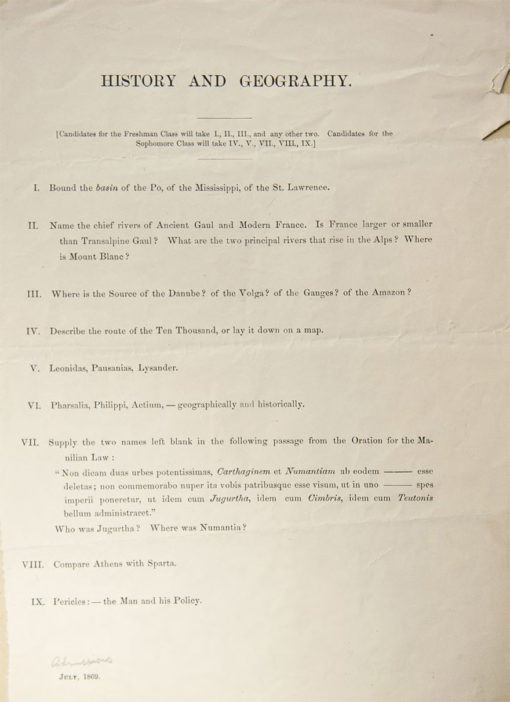

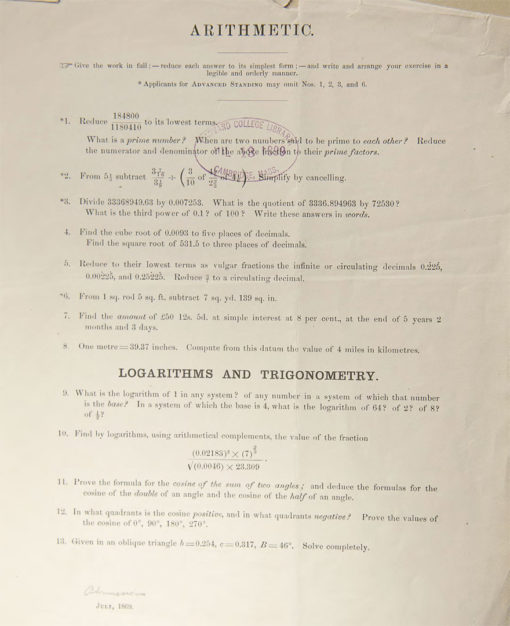

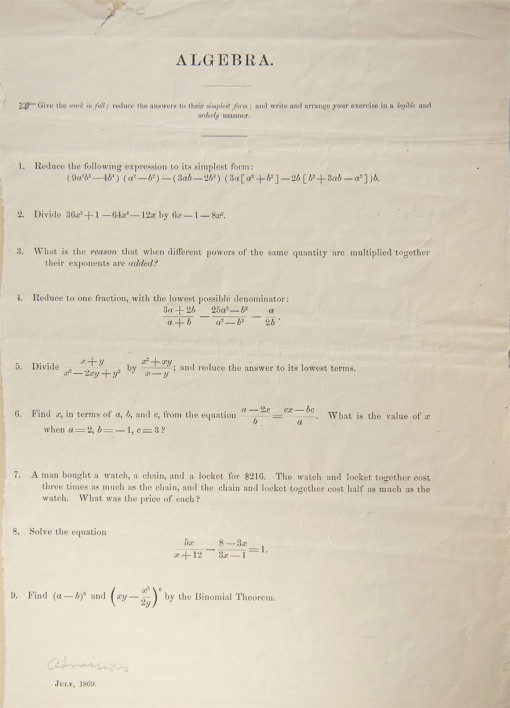

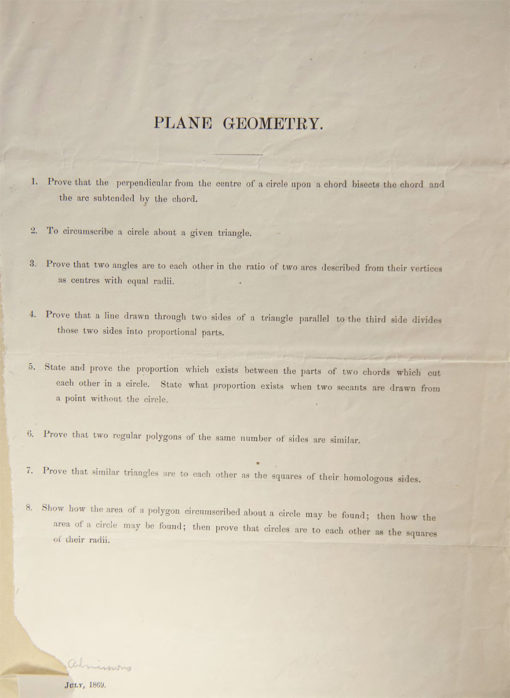

You can click on over to the article for advertisements from other top schools and other examples of the admissions practices of these days gone by. What really caught my attention was a PDF of the actual sample questions from the July 1869 Harvard entrance exam.

Take a look at the pages below (click to view large).

There is no chance in hell that I would have passed the Latin and Greek portions of the test. After all:

Harvard’s literature from the 1869-70 school year noted that incoming freshmen were expected to know how to write in Latin and Greek “with the accents” and needed to demonstrate knowledge of “the whole of Virgil,” Caesar’s Commentaries, and Felton’s Greek Reader or comparable texts.

The geography and history section doesn’t seem so bad — aside from question V: “Leonidas, Pausanias, Lysander.” Errr…what exactly are they asking? — I’m pretty confident that I would have done well on this section if I were to have taken the test straight out of high school.

The math section really surprised me, because…well, I suck at math and I haven’t touched anything aside from basic arithmetic since the age of 18. But I was able to figure out all the questions without hesitation. I was actually pretty proud of my aging brain.

How would you have done on this entrance exam from 1869? Is there anything that surprises you about the test?

![A Semi-Lazy Post [An Update in Pictures] 295074_840307983955_108813324_n](https://www.geekinheels.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/295074_840307983955_108813324_n-130x130.jpeg)

Christine

I took four years of Latin, so I would’ve done okay with this portion of the exam, but I’m very surprised that it’s a part of the Entrance Exam! Talk about really qualifying your candidates!! As for the Greek portion… I would’ve totally bombed it!

Susan

This confirms that I made the right choice going to a state school! And I thought the SAT’s were rough…..

Syderia

About question V, I think they’re simply asking for a (short ?) essay about these three guys.

mindy

in math question.. “write the answer in WORDS” .. AHHAHAHAHA

Sucks that kids couldn’t use TI-83 (and yes i know quoting TI-83 puts me in the “older population”… but it’s okay because i’m making fun of EVEN older people born in 1800’s.. hehe)

Hanna

I guess I’m surprised how much knowledge has advanced:)

LatteLove

I wonder what undergraduate institutions would look like (and graduates, for that matter) if these were still the entrance standards!

I could answer the Greek portion pretty well because I’m currently taking a class in Ancient Greek. I could maybe guess a couple words in Latin because I used a Latin vocabulary curriculum for one year in high school.

Michael

I took my B.A. in Classics, so did pretty well actually. Had I majored in anything else, I would have been screwed just like most people of course.

Interesting to see that high schools back in the day not only taught Greek, but apparently even some basic Greek prose composition. You can get your B.A. in Classics without doing any prose comp in many colleges. I only had Latin prose comp, but still I managed, especially since they gave suggestions.

Even so, there were a few curveballs in the detailed grammar questions. Actually, I have a hunch here: many 19th century universities just set block lines of Greek and Latin excerpts as sight translation exams. Harvard may have wanted to make it ‘easier’ by instead having basic prose composition and a bunch of syntax and morphology questions–but I actually would have done better had they just given me some Virgil, Cicero, Xenophon or Plato to translate. Remembering when to use ‘ne’ vs. ‘ut non’, or how to decline the irregular noun _neos_ can be tricky.

The ancient geography presumes you’ve read things like Caesar of course but also Xenophon’s _Anabasis_ (relatively simple Attic Greek and so it has always been commonly used to teach students); and also Sallust.