Studies have long shown that people of different cultures act differently, but a paper published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology indicates that culture even affects our cognition.

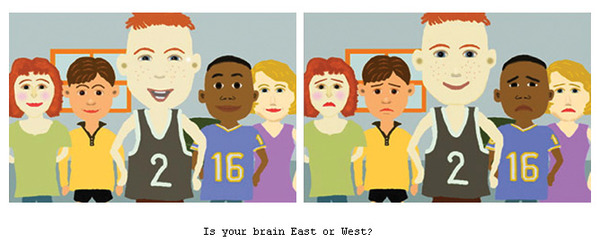

Take a look at the images above and try to interpret the overall emotion of the picture. Do your eyes linger on the center man in the foreground? Or do you consider the people in the background more?

“North Americans try to identify the single important thing that is key to making a decision,” explains Dr. Takahiko Masuda, the study’s author, over the phone from his office at the University of Alberta. “In East Asia they really care about the context.” He studied the eye movement of Americans and Japanese when analyzing a picture of a group of cartoon people. When asked to interpret the emotion of the person in the center, the Japanese looked at the person for about one second before moving on to the people in the background. They needed to know how the group was feeling before understanding the emotion of the individual. The Americans (and Canadians in subsequent studies) focused 95% of their attention on the person in the center. Only 5% of their attention was focused on the background, and this, Dr. Masuda points out, didn’t influence their interpretation of the central figure’s emotion. For North Americans the foreground is all-important.

Dr. Masuda is quick to point out that Americans and Japanese are physiologically the same. The difference in eye movement is tied to the roots of our respective cultures. When trying to explain the natural world, the Ancient Greeks – the founders of Western civilization – tended to focus on central objects and sought to explain their rules of behavior. Funnily enough, Aristotle thought a rock had the property of “gravity.” It didn’t occur to him that a system was working its powers on the rock. The Chinese on the other hand took a more holistic approach. They believed that everything occurred within a context, or a field of forces, and thus they unraveled the relationship between the moon and the tides.

Western cultures have placed importance on unique and strong individuals since the days of the ancient Greeks. In contrast, Eastern Asians place emphasis on the community and the big picture.

I’m not sure about other Eastern Asian languages, but even the Korean language reflects the priority of the community. For example, the word “my” is rarely used in familial context. Instead, you are more likely to hear things like “our father,” “our mother,” and even “our baby” (even when the speaker is not the parent).

So what do I see when I look at the image above? Although I consider myself pretty Americanized (and I have lived in the U.S. for 23 years vs the 7 in Korea), I caught myself considering the background almost immediately.

I wouldn’t say one viewpoint is superior to the other, as the author suggests at the end of this Adbuster article. The Western stress on rugged individualism has churned out some of the best leaders, thinkers, and innovations in history. At the same time, such a “me me me” attitude can be detrimental to the needs of the minority and personal relationships.

What do you see? Is your brain east or west?

Via Neatorama.

I like books, gadgets, spicy food, and art. I dislike shopping, hot weather, and the laws of entropy. Although I am a self-proclaimed computer nerd, I still have a love for handbags and makeup... and I am always teetering on high heels. To learn more about me, visit the

I like books, gadgets, spicy food, and art. I dislike shopping, hot weather, and the laws of entropy. Although I am a self-proclaimed computer nerd, I still have a love for handbags and makeup... and I am always teetering on high heels. To learn more about me, visit the

I’ve lived in the US my entire life and I can’t even name an ancestor that isn’t American and I immediately looked at the people in the background. Weird. I wonder if there is a gender component as well…

This is so interesting. I looked at the people in the background, but I wonder if part of that is maybe my observational thinking?

My brain is East. In just seeing the picture on my google reader, I was instantly drawn to the community/background before assessing what the person the forefront was feeling. On the left, the main character was satisfied that all were in agreement. On the right, everyone was upset because the main character got what he waned without respect to how others felt.

I, too, looked at the background more than the foreground–I’m a totally European-descended American, but my family has always had more of a culture of looking at the context and considering groups rather than individuals. I wonder if it has something to do with cultures that value extended family living together and functioning as an identifiable unit. Like, my parents and I were one family unit, but we didn’t exist outside the context of my grandparents and aunt, because we all lived close, my dad’s mom lived with us, my aunt lived with my mom’s parents, and it always went without question that resources (particularly financial) were to be used for the good of the whole family. Sometimes that meant a lot of money for an individual’s benefit, but each person and group gave and received as was needed.

Or maybe there’s a divide based on people who are more likely to take note of a negative emotion? I find myself glancing past the first picture in general, and I think it’s because the first group is all happy (read: satisfied; they don’t need anything) and the second group is mostly unhappy. Are some people more likely to focus only on happy people (whether out of a positive, optimistic reaction or a negative, narcissistic one), and others are more likely to focus on unhappy people (for better or worse, out of a desire to help or fix problems)?